This story on the regulatory framework behind unmanned aerial systems, or UAS, by Ian Thompson first appeared in the October 2019 edition of Australian Aviation.

In the past five years the use of unmanned aerial systems (UAS) has grown dramatically in Australia and new operational demands are emerging across quite different user segments. While there is rapid growth in small UAS that are quite inexpensive and easily acquired by members of the public, other operators are looking to introduce large sophisticated systems. New services involving the movement of retail products and passengers around urban areas are also now emerging. This broad range of UAS operations requires the development of new safety regulations and new traffic management technologies. (It should be noted here that the term UAS can be used interchangeably with remotely-piloted aircraft system (RPAS) or drones.)

Until quite recently, UAS were mostly used for defence purposes. They are now being used in roles that support government authorities such as observing border areas, supporting maritime surveillance and conducting observations for fisheries and forestry agencies. Commercial UAS use is now very broad, including inspecting infrastructure, farming, surveying, real estate and many more.

UAS can be generally categorised into three groups:

Certified operations involve UAS of greater than 2kg, which undertake commercial operations, and require the company and the operator to be licensed;

Excluded operations, which can include UAS of greater than 2kg, only fly over an owner’s property. UAS use by farmers falls within this category, and;

Recreational operations involving UAS of less than 2kg.

At present, there is no definitive data about the number of UAS in each category. Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) records show that there are 1,200 certified UAS operators in Australia, with each almost certainly having more than one machine. It is estimated that 11, 000 to 12,000 UAS fall within the excluded category. UAS falling within the recreational category could number anywhere between 500,000 to one million machines.

To understand the size and scope of the sector, CASA will begin a national registration of all drones

at the end of this year.

Michelle Benetts, Airservices executive general manager customer service enhancement, reports that the compound annual growth rate of the RPAS market from 2015 to 2018 was 120 per cent. This market is expected to grow at 20 per cent annually for the next five years. She said that the size of the Asia Pacific RPAS market is now the same as the Americas and is predicted to grow at a much faster pace which means that it will be the largest RPAS market within five years.

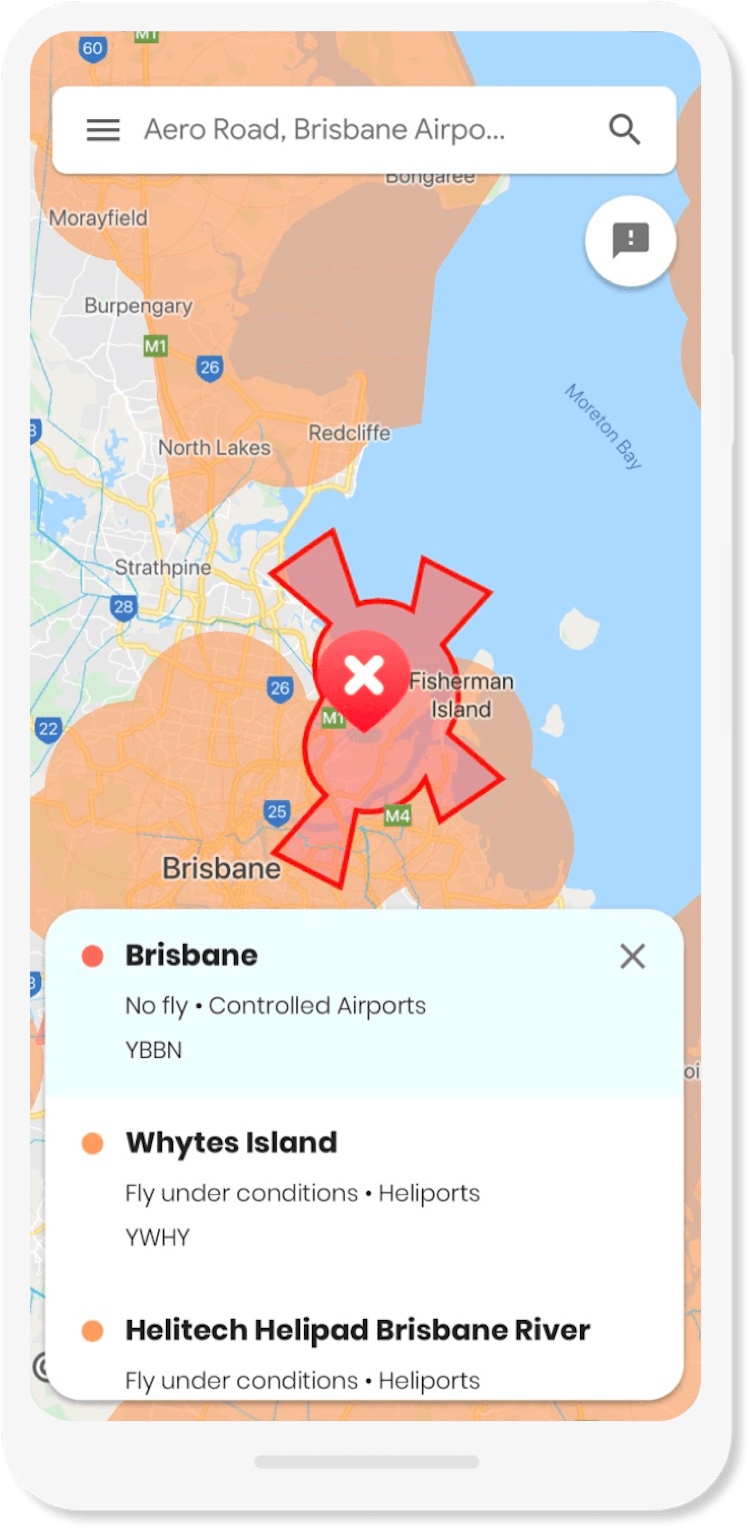

In very broad terms, drones can operate during daylight and up to 400ft above ground level provided

the operator remains within visual line of sight of the machine. It cannot operate closer than 3nm from a controlled aerodrome, in restricted areas, over populous areas or within 30m of people not involved in the operation of the drone. Operators can obtain some relief from some these restrictions by achieving certification of their organisation and pilots, as well as meeting CASA risk mitigation requirements.

Concerns have been raised about UAS flying close to passenger aircraft or in areas that prevent operations at an airport. Australian Transportation Safety Bureau (ATSB) data shows that the number of safety occurrences involving UAS have been increasing since mid-2015, probably coinciding with the rapid growth in recreational units. The greatest number of safety occurrences since 2014 (68 per cent) involved near encounters with manned aircraft. More than 70 per cent of these encounters took place above 1,000ft – 50 per cent in the Sydney basin area.

Greg Hood, ATSB chief commissioner, says that while no collisions have occurred with manned aircraft, UAS are presenting an emerging and insufficiently understood transport safety risk. He says that ATSB reviews RPAS collision research quarterly to assess whether they pose an unacceptable risk to manned aircraft. If such a risk is determined, the ATSB will notify CASA and the broader industry.

(By way of context, the ATSB notes that wildlife strikes have been a greater hazard to aircraft than RPAS. Between 2017 and 2018 ATSB data shows there more than 16,000 confirmed bird strikes in Australia, nine of which resulted in minor injuries to pilots or passengers.)

Since the beginning of 2019, CASA has undertaken work to better understand drone operations as well as their level of compliance to regulations. Peter Gibson, CASA spokesperson, explains: “A contractor has been engaged to monitor drone operations around major capital city airports. CASA has also used drone monitoring equipment at locations where they could be used inappropriately such as large public gatherings. The goal is to use this information to help CASA develop the most effective approach possible to drone safety regulation and enforcement. Data to date has indicated that while most drone operators comply with regulations some non-compliance has been identified. The monitoring technology enables the location of both the drone and the controller to be determined. When an inappropriate drone operation has been identified we can then investigate to determine if the regulations have been breached and issue a penalty, if that is appropriate.”

The UAS industry says that it faces three main issues, namely:

Access to Australian airspace by drones of all sizes;

Illegal operations, which have the potential to harm others in the industry;

The impact of noise, safety and nuisance, which could limit public acceptance of these operations and industry growth in Australia.

Greg Tyrrell, Australian Association for Unmanned Systems (AAUS) executive director explains: “Access to airspace is the most pressing issue facing the industry. Australia was the first country to regulate drones in 2002. While technology has dramatically changed, regulations have not evolved to match. Regulatory initiatives have largely been targeted at the burgeoning recreational sector. Pre-existing operators using large sophisticated drones have been largely neglected and there seems to be no regulatory pathway to accommodate the advancements that have occurred. Two of these concerns are the certification of large drones and beyond visual line of sight (BVOS) operations.”

Some of the large drones that will be introduced into Australia by Defence in the coming years will also have important civilian applications. At present, there is no process globally to undertake the certification of drones with a maximum weight exceeding 150kg.

“We are concerned that there is no pathway and seemingly no visible work being undertaken by CASA to define a certification process” asserts Tyrrell. “These large drones cannot fly within Australian airspace without being certificated. It seems that CASA will follow the work being undertaken in the USA and Europe, before implementing a certification process for Australia. This could take years.”

The capability to undertake beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations is essential to the growth of commercial operations. BVLOS involves drone operations being undertaken beyond the sight of the controller. Before approving BVLOS operations, CASA must be satisfied that no risk of collision between drones and manned aircraft exists, and there cannot be a risk to people in the event that a drone crashes to ground.

Applications including infrastructure inspection, mining and agriculture are ideally suited to BVLOS operations. In Australia, these activities frequently take place in very remote areas in low density airspace, well clear of population centres. Commercial delivery of products to customers in urban areas, however, are also reliant on being able to operate BVLOS.

The major concern preventing BVLOS operations is the inability of drones to see and avoid other airborne traffic. Large sophisticated drones being introduced by Defence have the technologies to detect other traffic, such as onboard radar. Small and medium sized drones don’t have this capability.

Tyrrell says: “The inability to see and avoid other aircraft makes operator certification difficult and places considerable limitations on the commercial applications that drones can perform. A government mandate requiring ADS-B (Out) fitment for all VFR aircraft would go a long way to overcome this issue. This fitment would allow the drone controller to see all manned aircraft in its vicinity and greatly increase the scope of operations, particularly in remote areas. It enables drones to be fully integrated with manned aircraft operations. Cheap ADS-B avionics, for as little as $1,000, are now available.”

In the recreation UAS sector, DJI – the manufacturer with up to 80 per cent of this market – is intending to fit drones with ADS-B (In). It will provide the drone controller with a traffic picture of aircraft with ADS-B equipment in its vicinity. This capability provides a traffic picture of manned aircraft for drones operating within or near controlled airspace. Manned aircraft fitted only with ADS-B (Out) surveillance technology, however, cannot determine the position of the UAS. It places the onus on the drone controller to keep the machine clear of manned aircraft.

BVLOS operations are categorised by CASA as being either simple, moderate or complex. They require the drone operator to complete various levels of a CASA risk assessment before gaining approval to operate. Simple operations take place close to the controller with the drone not being visible for only small periods of time. Moderate operations take place in remote airspace that is clear of people, controlled airspace and VFR routes with drones operating BVLOS for longer periods. Simple are approved by CASA locally, while moderate operations are approved regionally with central scrutiny. Moderate operations require the completion of a ‘light’ version of the CASA risk assessment process.

Complex BVLOS operations require the operator to complete a full specific operations risk assessment (SORA). This risk assessment methodology has been adopted by 59 countries. SORA involves the operator completing responses to 10 criteria, mostly requiring quantitative data to demonstrate how various risks will be mitigated. This risk assessment depends upon the specific characteristics of the operating environment. Operator responses to SORA are assessed by a centralised team in CASA before receiving approval. This risk certification process is also required before drones can operate over populous areas. Approval for complex BVLOS operations are not common, with only 11 having been approved to date by CASA.

The use of unmanned traffic management (UTM) systems are an integral component of complex BVLOS operations. These systems perform two main functions. They enable drone flights to be planned to keep clear of terrain and obstacles. The UTM also communicates with other systems to plan and de-conflict from other flights that will operate within a shared block of airspace. CASA approval is required before BVLOS operations can take place within a specific block of airspace.

UTM systems are developed, primarily, to manage drone operations taking place below 500ft above ground level. Traditional manned aircraft operations normally do not operate below 500ft, unless they are landing or taking off or within special use airspace. An exception is helicopter operations. It could become necessary for UTMs to have information about helicopters that may operate through this low-level airspace to prevent collisions with UAS.

At present, multiple UTM systems are available, which need to be integrated with each other to exchange information about drone flight paths that may conflict. Although these systems have been developed in Europe and North America, Thales is cooperating with Telstra to develop communication systems for drones in Australian low-level airspace. Decisions are inevitable about the capabilities required of UTM systems for Australian operations. In the longer term, UTM will almost certainly be integrated with air traffic management technology platforms to merge manned with unmanned operations.

Bennetts says that Airservices is exploring surveillance systems and data integration platforms to support ongoing safe operations as this sector grows. Airservices’ OneSKY ATM system, presently undergoing development, will require integration in the future with UTM surveillance pictures. It is seeking to explore other surveillance systems that can track aircraft and drones within controlled airspace. The most significant challenge that Airservices faces is coming to terms with the breadth of developments taking place in the management of drone operations so it can develop a solution that meets Australian circumstances.

Air traffic control procedures can be prepared to enable drones to enter controlled airspace and land at an airport. Tyrrell believes that it will be mainly larger drones that will seek approval to operate within controlled airspace. It is likely that gaining the necessary certification to operate over populous areas will present the most significant barrier to drone operations at city airports, not any problems in complying with air traffic control procedures.

Arguably, the most significant commercial drone operation at the moment is being undertaken by Wing in suburban Canberra. Wing is owned by Alphabet, the American parent company of Google. It began operation in 2013, initially with a trial undertaken in Queensland, near Warwick, where the first commercial deliveries were taken to a local farmer. Phil Swinsburg, Wing’s global head of flight operations explains “Since the initial trial we have undertaken around 80,000 flights testing our system. We have progressively undertaken a certification process in consultation with CASA, coinciding with the gradual development of our capability.”

Following the Warwick trial, a small commercial operation began on the outskirts of Canberra. It involved delivering products to six customers but only operating to visual line of sight standards. The operation subsequently moved to the rural area of Royalla, NSW then on to Bonython in the ACT. “We sought deliberate outcomes from the services provided in each of these areas” said Swinsburg. “In consultation with CASA, we progressively evolved from a relatively rudimentary drone operation to now being able to undertake services using BVLOS over populous areas. Most recently we moved to Mitchell to deliver commercial products to the Gungahlin suburbs in the north of the ACT and last month announced our intention to establish operations in Logan, Queensland.”

Wing has 15 commercial partners, generally small businesses, ranging from hot coffee makers to golf equipment. Operations are performed during daylight hours from Wednesday through Sunday each week. After placing an order via a mobile application, the goods are received by the customer within 10 minutes. The length of flight is generally four minutes. Drones operated by Wing have a wing span of 1.2m and a maximum weight of 7kg. They use 14 propellers and fly at a maximum airspeed of 120 km/h.

CASA issued approval to Wing to operate within a geographically defined flight area to a maximum height of 400ft above ground level. The drones are operated by a CASA-certified controller. Each controller is approved to supervise the operation of a number of drones simultaneously.

“Our own ‘cloud’-based UTM is used to prepare the flight plan and undertake any airspace de-confliction” says Swinsburg. “The flight plan process involves defining the terrain and obstacles along the route, which sets the minimum altitude that can be flown. We obtain this information from Google as well as from our own obstacle surveys. Other parameters, such as wind information, are incorporated to enable the flight to take place on the most efficient route. The route flown by the drone is very accurate, not more than two metres either side of the defined flight path. Our goal is to optimise the operational efficiency of the flight. Consequently we generally fly at cruising altitude of 20-30 metres above ground level and it is uncommon for the drones to fly to our highest approved level of 400ft. Airspace is reserved for the duration of the flight, based on the time the drone will operate and its actual position. This airspace reservation process ensures that a flight is de-conflicted from other drones. It also enables large numbers of drones to operate in close proximity. We would like other operators to use our UTM, which utilises open architecture, so that other drones are known and their flights can be de-conflicted.”

The operation is fully autonomous, which means the controller is only managing airspace or emergency situations. All activities associated with the flight are conducted automatically in accordance to the flight plan, without additional input from the controller. At present the drones do not have ADS-B capability. In the future, however, it is likely that ADS-B (In) will be fitted to provide the UTM with position information about aircraft in the vicinity of the drone operation.

The Wing operation has received noise complaints from residents around Bonython. While noise approval was issued for the operation by the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development this decision is subject to further review. To overcome these residential noise concerns Wing has modified its propeller system and pays attention to the hours and days of operation.

Uber Elevate is also soon to begin early operations in Melbourne. It will provide services between Melbourne city and the airport using an autonomous UAS. A trial is scheduled to commence during 2020 with operations to begin in 2023. For the foreseeable future, however, a pilot will be on board the UAS monitoring its operation and be ready to intervene if needed. It could take 10 years or so, involving a vast number of flights, before an autonomous operation will become a reality. At a practical level, Uber Elevate could be considered similar to a helicopter service operating from one or more designate landing areas in the city and airport, flying on predefined flight paths. It will operate via its own UTM system. The UTM may need to incorporate data about random helicopter operations that take place around the Melbourne central business district, particularly those operating along the Yarra River. In a similar manner to Wing, it seems likely that Uber Elevate will organically grow its operation as it progressively meets CASA risk mitigation requirements.

The use of drones has grown substantially in the past five years and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Commercial operations over urban areas are just commencing but they will almost certainly increase the exposure of the public to UAS operations. Much work is needed by governmental agencies to prepare regulations and service deliver mechanisms that meet the requirements of these operations.

This story first appeared in the October 2019 edition of Australian Aviation.