To mark the 60th anniversary of Qantas starting jet operations with the Boeing 707 on July 29 1959, this story from the Australian Aviation archives comes from March 2007, when Jeff Watson wrote about the return to Australia of the airline’s first jet aircraft VH-EBA City of Canberra. Watson was on board the aircraft for the delivery flight.

On December 16 2006, Qantas’s very first jet aircraft, Boeing 707-138B City of Canberra, landed at Sydney after a 14,000nm (25,950km) journey from England. It was the culmination of the most complex restoration project ever undertaken by Australians . . . most of them retired Qantas engineers in their 60s.

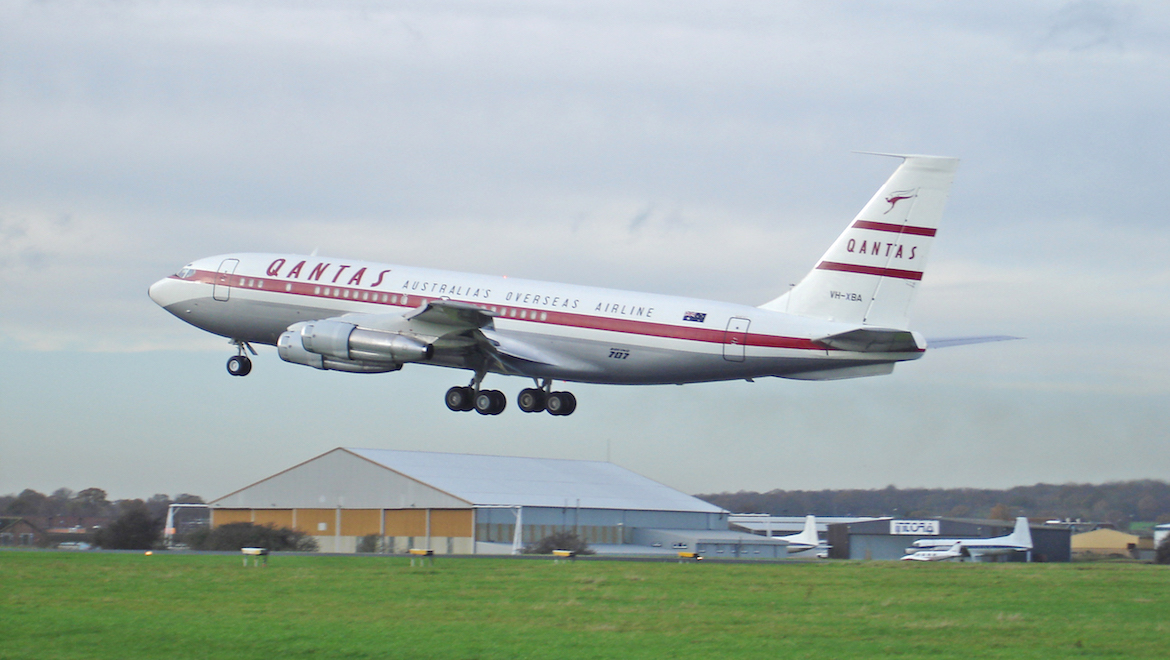

In the dying light of an English winter day a smoky trail appears in the pink sky. As I stand and watch it gets nearer and resolves into an Australian icon. It is Qantas’s first jet airliner, a Boeing 707-138B returning to Southend airport after its first test flight over the North Sea.

A patient knot of plane spotters rugged up against the cold gives a small cheer as Captain Roger Walter makes a perfect landing on Southend’s pocket sized runway. This is an emotional moment for the hard working retired Qantas engineers who have got the aircraft back into the air.

Bringing back to life an extinct species was never going to be easy. VH-EBA had sat on the ground at Southend-on-Sea for six years, its white roof covered in blotchy mildew. In the absence of a buyer it was destined to be scrapped. Then BAE Systems, the owners, agreed to sell the aircraft to the Qantas Foundation Memorial to be displayed at the museum at Longreach.

VH-EBA first flew on March 20 1959 and was delivered to Qantas on July 16 that year. It stayed behind in Seattle for flight tests, its sister aircraft VH-EBB becoming the first 707 to arrive in Australia. These were the first 707s sold outside of the United States.

Between 1967 and 1969 the 138Bs were phased out to be replaced by the longer bodied 707-338Cs.

VH-EBA went to Canadian airline Pacific Western and became CF-PWV. Later converted into an executive aircraft it became the personal transport of Prince Bandar of Saudi Arabia and spent much of its life flying between Riyadh and Washington DC. The aircraft had flown a total of 60,000 hours by the time it arrived at Southend, but for the last year of its life with the Saudis it flew only 38 hours. For the duration of its test flights and delivery flight to Australia it was now known as VH-XBA (the VH-EBA registration now flying on a Qantas A330).

This was one of the most ambitious aircraft restoration project ever undertaken by Australians. A team of 20 engineers led by Peter Elliott travelled backwards and forwards between Australia and Southend from June until December 8 2006 when the aircraft left for Australia.

Most of the engineers were retired from Qantas; others were recruited into the team from Boeing at RAAF Amberley. Collectively the Qantas boys have 441 years experience in the business.

The restoration of the aircraft took more than 15,000 man hours and was only made possible by a grant of $1 million from the federal government’s Department of Environment and Heritage.

Many other companies including Qantas, Boeing, Goodyear and ATC Lasham contributed significant cash and kind to the project.

When the aircraft was first inspected it was found to be in surprisingly good condition despite the fact that it had been standing in the open for six English winters. The wing spars were examined and found to be excellent, a tribute to the sturdiness of the original design.

A major problem was the corrosion found in the tail. Twelve bird nests were removed from the base of the fin and rudder, some complete with eggs! Added to this there was a fist sized hole in the base of the rudder. The 800kg fin and rudder were removed and re-skinned, then painted and balanced before being re-installed.

The rudder is the only flying surface on the 707 to be servo assisted. The rest are operated by conventional pulleys and wires, a reminder of how basic the 707 was back in 1959.

Four new fuel control units were sourced and fitted to the Pratt & Whitney JT3D-1 turbofan engines. Number two engine was to give the team a major headache as it stubbornly refused to start. A team from Turbine Motor Works was brought in and took 12 hours to strip the engine. The trouble was traced to a waxy residue which had blocked the fuel nozzle filters. Originally Boeing 707s relied upon ground starting equipment, but at some time in its life VH-XBA had been fitted with an auxiliary power unit in the forward cargo hold which made ground starting much easier.

Cracks were found in the diffuser case; the engine was removed and taken away for welding. All this work was being carried out in deteriorating weather and the days were becoming shorter. Finally the Boeing was towed into the hangar to be painted.

The engines were hand painted with rollers and the tail masked to apply the flying kangaroo logo; it was starting to look like an aeroplane.

Southend Airport is a servicing base for many major airlines and with the end of the European summer the hangars were packed with partly dismantled aircraft. But the 707 project created great curiosity.

The idea of a bunch of retired Aussies getting a 47-year-old aircraft back into the air produced a warm feeling and generated a good deal of support from the locals. Most aircraft that fly into Southend go there to die; this one was most definitely going to fly again. But the project was fraught with many problems and sometimes the team returned to the hotel at night drained, despairing and exhausted.

The arrival of the flight crew in Southend lifted everyone’s spirits. In command was the ever cheerful Captain Murray Warfield who flew 707s with the RAAF and now flies 767s for Qantas.

The two other Captains, Roger Walter and Brett Phoebe both have wide experience on the 707. Roger was born in Tanzania and flew 707s with Air Zimbabwe; Brett flies 747 Classics and also flew 707s with the RAAF.

The younger members of the flightcrew, flight engineers Harry Hermans and Joe Plemenuk, were not born when VH-EBA was built! They had both flown 707s and C-130s with the RAAF.

Joe and Harry are not by any means small men but they regularly disappeared into the bowels of the aircraft – known as Lower 41 – via the hatch in the cabin floor. Not an experience for the claustrophobic!

Our sole flight attendant Karen Glass was given the task of ministering to the needs of 10 fairly demanding males. She was dressed for the flight in an exact copy of the Qantas flight attendant’s uniform of the period in pale green cotton with original buttons and a military style cap.

On November 30 the aircraft did its taxi tests and a high speed run down the runway to test the brakes and reverse thrust.

Then airworthiness manager Ken Cannane issued a Special Flight Permit giving permission for the first of two test flights over northeastern England and the North Sea. The aircraft was fuelled with 20,430kg (roughly half its capacity) for the test flight and lifted off smartly no more than half way down the runway.

It was a long time since anyone had seen the smoky trail from a 707 over Southend Airport, and for many there was a lump in the throat.

The flights revealed a few major problems which were to delay us even further, the most serious of which was the elevator which was stiff and did not have enough travel. The autopilot was not working either so a fresh search for spare parts was mounted.

Three alternative routes to Australia were planned, all via the United States and the Pacific. The engines were only Stage Two hushkitted (even though they were much quieter than the JT3C turbojets VH-EBA was originally delivered with) so we were denied access to airports like JFK. But Montreal, Halifax Nova Scotia, Philadelphia and Miami were all options.

Finally with the weather deteriorating in North America and snowstorms forecast for Montreal, the flightcrew decided to take the “beach route” to Australia via Dublin, Tenerife, Bermuda, Orlando, Los Angeles, Honolulu and Fiji. The longest flight sector was six hours from Honolulu to Nadi, Fiji and a minimum of at least one day was planned in each airport to allow unforeseen breakdowns to be fixed. The elevator was pronounced to be working satisfactorily. Ken Cannane issued the Certificate of Airworthiness and we were all set to go.

The 707 couldn’t take off from Southend with a full fuel load so the first leg was a short flight to Dublin. The day of departure was dull and overcast. A thin drizzle fell on the airfield but it did not dampen the spirits of the assorted engineers, plane spotters and TV crews who came to watch. The takeoff was uneventful and we orbited the airport to do a flypast for the media. Then it was time to head north west.

As we flew over the Irish Sea the weather cleared and it was bright and cold when we landed at Dublin. At Dublin we took on more fuel and were presented with a case of Guinness by the charming Gerry Guihen of the Irish Aviation Authority.

The next leg was a four-hour flight to Tenerife in the Canary Islands where we overnighted. This was followed by a long leg to Hamilton, Bermuda, where immigration were so disinterested in our arrival they didn’t even look at our passports.

As the trip wore on the aircraft performed better and better and systems which had been functioning erratically started working properly.

Spare parts for the autopilot had proved difficult to obtain and the aircraft was lacking the altitude hold mode which keeps the aircraft flying at the same flight level. Because of this air traffic control kept the aircraft out of the main stream of traffic.

Hand flying a big aircraft can be extremely exhausting for the crew but fortunately with three pilots the load could be shared.

Over the Atlantic the Boeing did not have approval to fly at altitude because of not being able to meet reduced vertical separation minima (RVSM).

The aircraft was restricted to 28,200ft which made it noisy on the flightdeck. Later over the Pacific the autopilot came good and the aircraft was allowed to climb to a more fuel efficient (and quieter) altitude of 33,000ft.

Aircraft that have been stored in very cold climates like England get moisture trapped behind plugs and instruments. Continual operation with power on, landing in warmer climates plus operating in drier air at altitude meant that the moisture was gradually being drawn out of the cabin.

In Orlando, Florida, a bit of Hollywood glitz was added to the adventure by the arrival of John Travolta who had swapped his Saturday Night Fever flares for a Qantas captain’s uniform. Travolta is a lifelong aviation enthusiast and has owned aircraft as diverse as an Ercoupe, a single engined Vampire and the MATS Constellation.

Ten million dollars a movie also means that he can afford to run another of Qantas’s 707-138Bs which has been remodelled as an executive jet complete with a double bed and showers, leather upholstery and cocktail cabinets. The two aircraft were parked side by side, VH-EBA being the first Qantas 707-138 and VH-EBM (now N707JT) the last.

In between movies Travolta roams the world as a goodwill ambassador for Qantas. The star of Grease and Pulp Fiction is passionate about aviation and has been flying since he was 16. He told me he is currently shopping for a P-38 Lightning and a DC-3 and has ordered one of the new single pilot Eclipse very light jets.

Orlando was followed by a six-hour flight to Los Angeles which was uneventful apart from a brief period of turbulence over the Rockies.

At Los Angeles the airport fire brigade lined their bright yellow tenders and gave us a royal send off with an arch of water spray. After that we were on the homeward leg as the aircraft re-traced the old route across the Pacific via Honolulu and Fiji. Cruising at Mach 0.82 we found something to relieve the tedium of a long overwater flight. From the cabin window we could see the black line of the pressure wave oscillating around Number 3 engine.

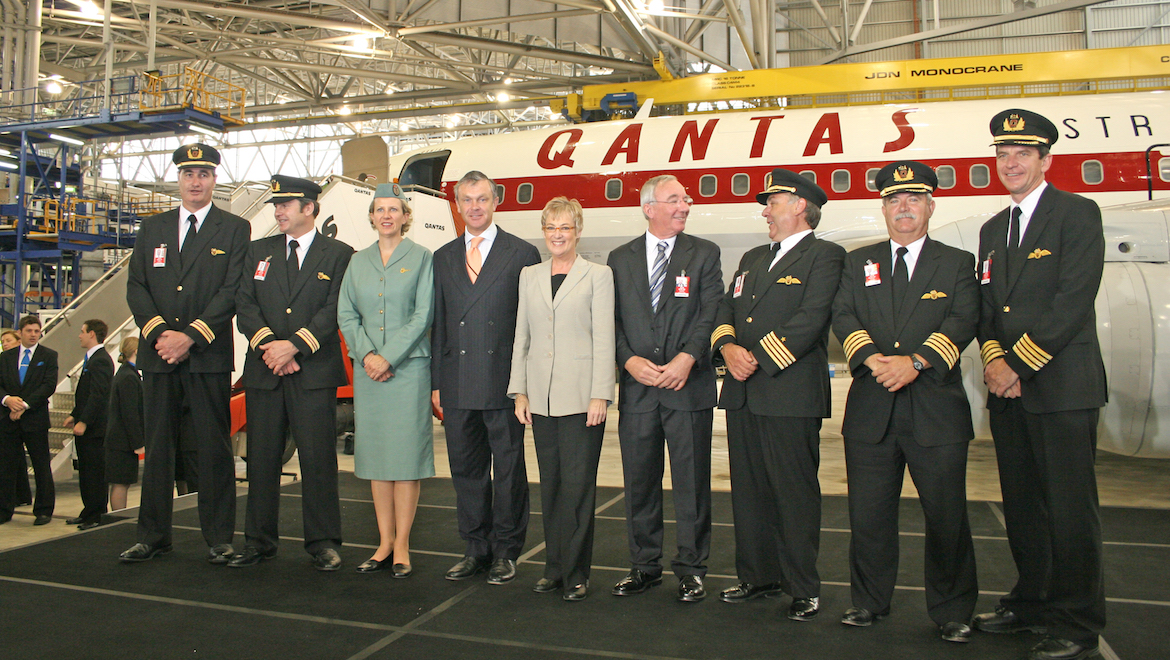

Finally on the morning of December 16 we touched down at Kingsford-Smith International Airport where we were welcomed by Margaret Jackson, Qantas chairman, and Senator Ian Campbell, Minister for Environment and Heritage. Both Jackson and Campbell hold the project dear; it would not have happened without them. I suspect there might also have been a tear in the eye of Warwick Tainton from the Qantas Founders Museum, one of the driving forces in the whole project.

“The team of volunteers has worked so hard for so long,” Murray Warfield said. “This is what they were waiting to achieve.”

After the miserable days in England with the weather, the awful food and a hotel straight out of Fawlty Towers, it all seemed worth it.

VH-XBA now rests in Sydney before hopefully completing a tour of select capital cities and possibly even making an appearance at March’s Avalon Airshow before it is retired to the museum at Longreach.

It has been undergoing maintenance and airworthiness checks which will hopefully see it receive special dispensation to conduct the tour, which would also allow the museum to raise additional funding so it can construct a suitable hangar for the 707 and its larger 747-200 stablemate already at Longreach.

VH-XBA deserves nothing less that a suitable home at the birthplace of Qantas. It is doubtful that we will again in Australia see the restoration to flight of such a large and complex aircraft. An aircraft that changed the way Australians travelled forever.

VIDEOS: A look at the return of Boeing 707 VH-XBA from Southend in England to Sydney from the mitaal380 YouTube channel.

This story first appeared in the March 2007 edition of Australian Aviation. To read more stories like this, subscribe here.

Mike

says:The last time I visited the Qantas Founders’ Outback Museum their B707-138B still carried the registration, VH-XBA. Having been on static display for now very close to 13 years, surely the museum aircraft could revert to “VH-EBA” which it originally carried in QANTAS service? (Please correct me if this has occurred since my visit!)

The argument I heard against changing the rego was that two aircraft cannot have the same registration. I completely understand that when the respective aircraft are both airworthy, however VH-XBA is not likely to ever fly again, so it’s a shame it cannot be displayed with the original registration.

Case in point is that the QFOM B747-238B, VH-EBQ , still wears its original registration despite the fact a QANTAS A330-200 currently flies with the very same registration letters.

Kerry Drew

says:I believe the captain Bruce who first flew this aircraft to Australia was a neighbour of our family, lived in Turramurra NSW.

Captain Bruce subsequently invited our family along with many others to a tour over the aircraft at Mascot.

A most memorable occasion for a 9 year old as I was at the time.

Disappointing that neither the captain nor the crew of that maiden flight failed to receive a mention.