This story about the engineering operations at Qantas first appeared in the August 2019 edition of Australian Aviation.

A few years ago, a Qantas engineer was called to one of the airline’s Airbus A380s in Sydney. A defect had been discovered in an emergency slide that needed to be addressed before the aircraft could be cleared for departure.

The task required the engineer to climb up a wheel well to disconnect a “cannon plug” to deactivate the slide. The instructions, according to the A380 aircraft maintenance manual, called for the engineer to “carefully go up through the opened body landing gear door bay to get access to the slide electrical connector”.

In practical terms, that meant climbing up the main wheels and over a horizontal beam before reaching up to disconnect the cannon plug with both hands.

The problem, which nobody had noticed or thought to highlight up to that point, was that the situation left a person at risk of falling from a height of five metres.

That was because the harness connect point was located aft of the gear and therefore incapable of providing protective support, while ladders or stands were also ruled out due to the position of the landing gear.

While any number of engineers to have previously performed this task all around the world had, metaphorically, shrugged their shoulders and moved on to the next job, the Qantas engineer raised a hazard report and the event was investigated.

The result was that six weeks later Qantas, in consultation with Airbus, came up with a new procedure where the slide could be deactivated at the local door controller inside the cabin.

Qantas engineering manager for training and competency Ian Weeks says this relatively minor change in procedures means the risk of falling inside the wheel well has been eliminated for every engineer working on that task.

“Now, nobody in the world has to go through that experience because our engineer notified us and then our fleet teams worked with Airbus to come up with a new solution to fix that problem for everyone,” Weeks told Australian Aviation in an interview in late June.

“One person who was doing that job identified that risk. If he had said nothing, we probably wouldn’t know that risk still even existed today. He was able to tell us about it, give us good information that we could then feed back and fix that for everyone.

“We’ve celebrated that good news because that is something that is bloody good for everyone involved.”

Weeks says the episode also represents the gold standard in the type of culture the company is trying to instil in its engineering department.

It is a culture where safety is the number one priority and employees, no matter what level they are at, feel empowered to raise issues confident in the knowledge they will be treated with the deserved attention and respect.

“Someone is putting this report in, not because they are trying to be painful but they are actually concerned and they want to raise it so that somebody else is not either put in that position or that it gets fixed,” Weeks says.

“The worst thing to we could do is ignore it because then the person goes ‘if you are not taking it seriously why would I ever put a report in again’.”

Qantas Engineering training for a new world

As an airline about to celebrate its centenary in 2020, Qantas has a long history.

It follows then that Qantas’s engineers are by and large an experienced lot. To illustrate the point, the average age of those working in line maintenance is 54 years old. Weeks himself has more than two decades at Qantas, having started as a licensed aircraft engineer.

For decades they have performed difficult tasks on sophisticated machinery every day based on procedures found in large printed manuals or microfiche.

While that system worked well, the arrival of next generation aircraft – starting with the A380 to Qantas in 2008 and followed

by the Boeing 787 first for the airline group’s low-cost carrier (LCC) subsidiary Jetstar in 2013 and Qantas itself in 2017 – has coincided with a change in how engineers are trained and how they access information.

Technology has played a major role with engineers issued with tablets that include QE:Touch, an app designed in-house that provides access to information and instructions on specific tasks, such as preparing an aircraft for departure during its 35-minute “turn” at the gate.

Similarly, diagrams and sketches in a manual have given way to video clips and digital illustrations on how to perform specific tasks.

While Weeks says there have been some teething problems along the way, everyone is making good progress with the transition.

“People with 40 years’ service in Qantas engineering are not rare, let’s put it that way,” Weeks says.

“They are now having to learn an entire new set of skills to allow them to work in a more modern digital age.”

VIDEO: A Qantas supplied instructional video for working on an Airbus A380 fuel pump.

As the veterans of the engineering workforce are making that transition, Qantas is also hiring young apprentices – the generation of so-called digital natives.

Fifteen new apprentices joined the engineering unit in 2018 after completing their training at Aviation Australia’s Brisbane campus.

What they lack in on-the-job experience is made up for in their familiarity around personal electronic devices, apps and the use of multimedia in learning new skills.

And that has created a dynamic where it is not only the old hands showing the rookies the ropes, but the rookies also teaching these long-time engineers a thing or two.

“You’ve got an engineer with 40 years’ experience teaching the younger person how to do a job or how to approach a job,” Weeks says.

“At the same time that 25-year-old person is teaching that person with 40 years of experience how to use the iPad to do theirs. It’s a great experience for both.”

A fresh look at safety

Aviation has always placed safety above everything else.

In terms of maintenance, the focus has been on preventing an error by having all the approved data, all the right parts, and – among other requirements – ensuring the materials needed are within their use-by dates.

While those principles have served engineers well over the years, the emphasis is now on safety for everyone and Qantas engineering has a set of 10 safety behaviour standards that guides all its work.

The standards include a risk identification tool called Take 5, ensuring effective communication and documenting all tasks in full.

Weeks says it is a list of 10 standards followed by each engineer working professionally for Qantas.

“We’ve got to make sure that we look at the overall safety picture, even when we have an industry that is so governed by time pressures,” Weeks says.

“The material that we are creating is both how you approach the job and how you approach it safely.”

VIDEO: A Qantas supplied instructional video on servicing the nose landing gear on the Airbus A330.

Qantas’s A380 cabin reconfiguration offers a real-life example of these principles being put into practice.

As part of the program, Qantas is installing a premium economy seat that includes an airbag in the back

of the seat, which is a change from the current version.

Therefore, those working on the seat need to be aware of the consequences of accidentally deploying the airbag.

“How do I get through to people that this is dangerous? The simplest way to do it is to show an airbag that’s being deployed and how quickly it does it,” Weeks says.

“I need to get the message through that if you are working on this system we need an exclusion zone around that so that if, for whatever reason the airbag deploys, you’re not going to hurt someone doing it.

“The material that we are creating is both how you approach the job and how you approach it safely.”

Human factors have also played a key role in the area of maintenance and training.

Weeks says Qantas engineering was in its fifth round of recurrence training on human factors.

“We’ve aligned behaviours with our human factors elements and training,” Weeks says.

“We linked those human factor elements with those safety behaviour standards.”

VIDEO: A Qantas supplied video on the correct procedures in the event of a fuel spill.

Integrating data

Consider the engineer mentioned earlier needing to prepare an aircraft for departure.

Previously, the job would have involved separately getting, from flight operations, the fuel load information, the latest weather forecasts from the Bureau of Meteorology, and downloading any aircraft communications addressing and reporting system (ACARS) messages that had arisen during the previous flight.

Now, thanks to the QE:Touch app, which was developed by a Qantas engineer, everything the engineer needs for the task – and much more – is available via tablet.

Weeks says the combination of experience and tech-savvy makes the job “easier and quicker.”

It represents a huge efficiency gain for everyone involved.

“What we are trying to do is really give the people the information that they need at the time they need it,” Weeks says.

“If you do a job safely and you do it right every time, and you give them all that information when they need it, it means that the likelihood of them getting it wrong decreases significantly. There is a huge payoff for that.”

New aircraft, new approach

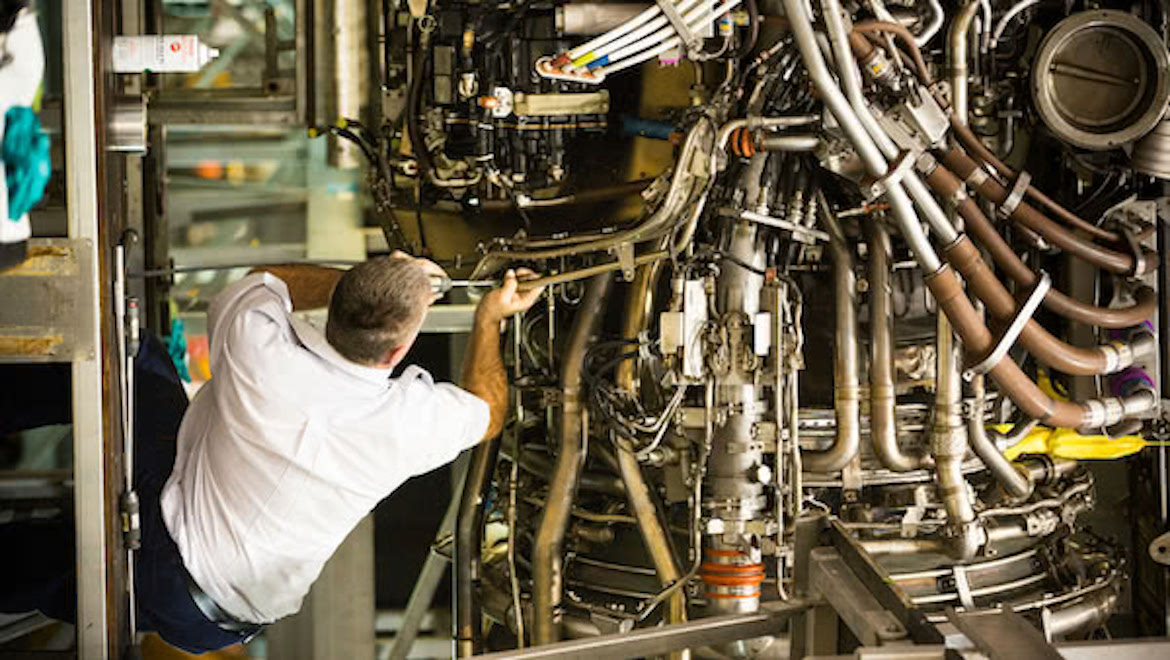

Weeks says the arrival of Qantas’s first A380 VH-OQA Nancy-Bird Walton was the first time the airline’s engineers had an aircraft that was fully integrated. And that meant a new approach to maintenance, which has continued with the 787-9.

“So when you go and replace a valve, not only do you need to go and replace the valve itself physically – undo the nuts and bolts and pull it out – but then you have to make sure the software that you load so you can talk to an aircraft is the same as well,” Weeks says.

“We had an introduction of that with the A380. The 787 just goes beyond that again. It is an entire next step. It’s a polar shift from traditional aircraft designs to composite structures, electric brakes and bleedless engines.”

Weeks says Qantas used the 787 theory training material from Boeing but had Jetstar engineers give the practical training on the aircraft to the Qantas engineers.

“We leveraged off what they had already learned so that they could give that peer-to-peer learning,” Weeks says.

“It’s just that validity of an engineer talking to an engineer.

“Understanding our engineering audience is important too. The majority of our staff are not office people so the communication approach needs to reflect this and provide the best opportunity for getting the message through.”

VIDEO: A Qantas supplied training video on the Boeing 787-9 thrust reverser.

This story first appeared in the August 2019 edition of Australian Aviation. To read more stories like this, subscribe here.

Stewart Corfield

says:I was interestEd in the engineering training videos. Having been a trainer in the TAFE area forover 30 years, I saw the advent of a lot of video training. I even made up some myself. One problem I noticed with these videos, which is common on a lot of training videos, is that the narrator is obviously reading from a script and consequently is going too fast for the serviceman to follow on the part. By continually having to find the pause button on the tablet and then going back to find the black or white lines then remembering what had to be done with them caused problems particularly with older operators. We had this problem in teaching how to use lathes, millers etc. Our solution was to either talk slower or pause for about 10 seconds to allow the relevant reference points to be found. However it is the way of the future.

Greg Stevenson

says:I was trained and worked for forty-two and a half years at Qantas; in Qantas Engineering. I started in 1965 and retired in 2008 in the position of Engineering Maintenance Coordinator. My entire working life at Qantas nearly equals half of its 100-year life and I’m proud of being an employee and still to this very day defend Qantas and speak to everyone how much I enjoyed my years working for Qantas.